In a recent real-world scene, a customer at a post office paused a queue by waving a phone, and a ChatGPT reply claimed there was a “price match promise” on the USPS website. No such promise existed, but the customer trusted the AI’s asserted knowledge over the clerk’s memory, as if consulting an oracle rather than a probabilistic text generator guided by human prompts.

This episode highlights a core point: AI chatbots do not harbor fixed personalities. They are prediction machines that generate text by matching patterns in training data to your prompts. Their outputs depend on how you phrase questions, what you ask for, and how the system is tuned, not on a stable, self-directed belief system.

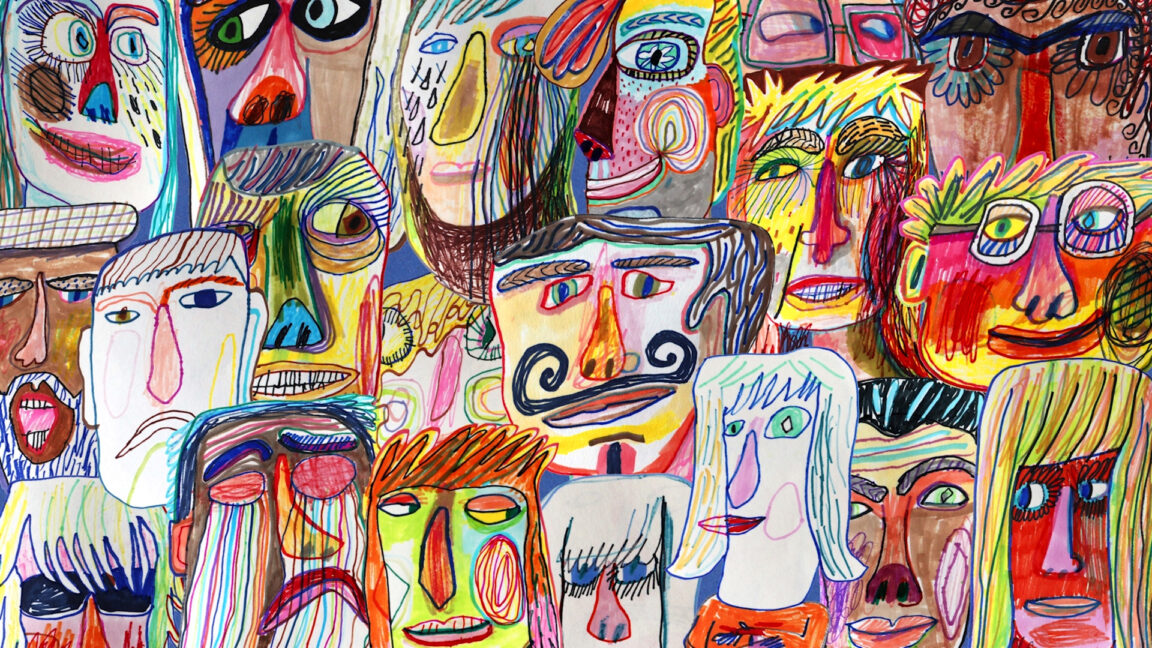

The article argues that millions of daily interactions encourage a false sense of “personhood” in AI, treating the system as if it has a persistent self and long-term intentions. It coins a phrase—vox sine persona, voice without person—to remind readers that the voice in your chat window is not the voice of a person, but a reflection of statistical relationships between words and concepts.

Beyond the philosophical confusion, there are practical risks. When users treat an AI as an authority, accountability becomes murky for the companies that deploy these tools. If a chatbot “goes off the rails,” who is responsible—the user’s prompts, the training data, or the company that set the system prompts and constraints?

The piece emphasizes that interactions are session-based: each chat is a fresh instance with no guaranteed memory of prior conversations. Memory features some chat systems offer do not store a true personal history in the model’s mind; instead, they pull in stored preferences as part of the next prompt. That distinction matters for understanding what the AI can and cannot do, and for avoiding overestimating its capabilities.

![[AS52888] ASN52888 (4 probes)](https://r2.isp.tools/images/asn/52888/logo/image_100px.png)

![[AS2716] Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul](https://r2.isp.tools/images/asn/2716/logo/image_100px.png)